On Time and Voice: thoughts on “rules” for artists working in and with communities

Artists often establish rules for themselves, guidelines they follow to make their work – self-imposed parameters, or limitations, or conditions. In recent months, several experiences have given me reason to consider ideal rules for an artist to work in a community that is not their own:

• attending a beautifully executed, contemporary dance piece on homelessness, choreographed and performed by a professional dance company in the streets and alleys of Over-the-Rhine;

• an opportunity to develop a space in the community for neighborhoods adjacent to University of Cincinnati, where neighbors could voice their needs and concerns in relationship to UC (prompted by the shooting death of Samuel DuBose by UC police officer Ray Tensing, and as a sequel to drawn, an art space on campus in August created in response to this devastating event);

• having been selected to develop a work titled Outside/In that looks at Washington DC’s unique political landscape in a three-part guided walk led by DC folks that situates the exploration through national, community/advocacy org, and resident perspectives;

• an invitation to sit on a panel at Wave Pool Gallery in Camp Washington to discuss “the line artists/arts centers walk between being a positive force in engaging diverse, changing communities, and being a force of gentrification.”

And I just keep thinking: TIME. This is one condition that seems essential to honest, effective artistic work in and with communities. It takes time to form meaningful relationships marked by trust and mutual connection and benefit. IMHO, at least one year. And not one year to complete the work, but to meet and get to know the people who do live in a place; to learn the lay of the land; to identify and understand the narratives, the social, racial, civic, economic and political forces at play; to listen to how people see their community vs. how outsiders or people in power do. My work in Over-the-Rhine here in Cincinnati started in January, 2014. Almost two years later, I’m still learning this stuff, even as I engage with OtR collaborators to do the work. In my organizing experience (I started as a young idealistic thing in 1987), presence, and experiences together over time, are important ingredients for the kind of trust that’s essential to any work if it is to benefit the community and isn’t just to advance the reputation or career of the organizer. Same goes for social practice artists.

I’m not the first person to think or say this. The term “parachuting artist” exists because people are asking this question and coming to similar conclusions.

Even when we invest a substantial amount of time, though, there’s a next critical question, and it’s that of VOICE.

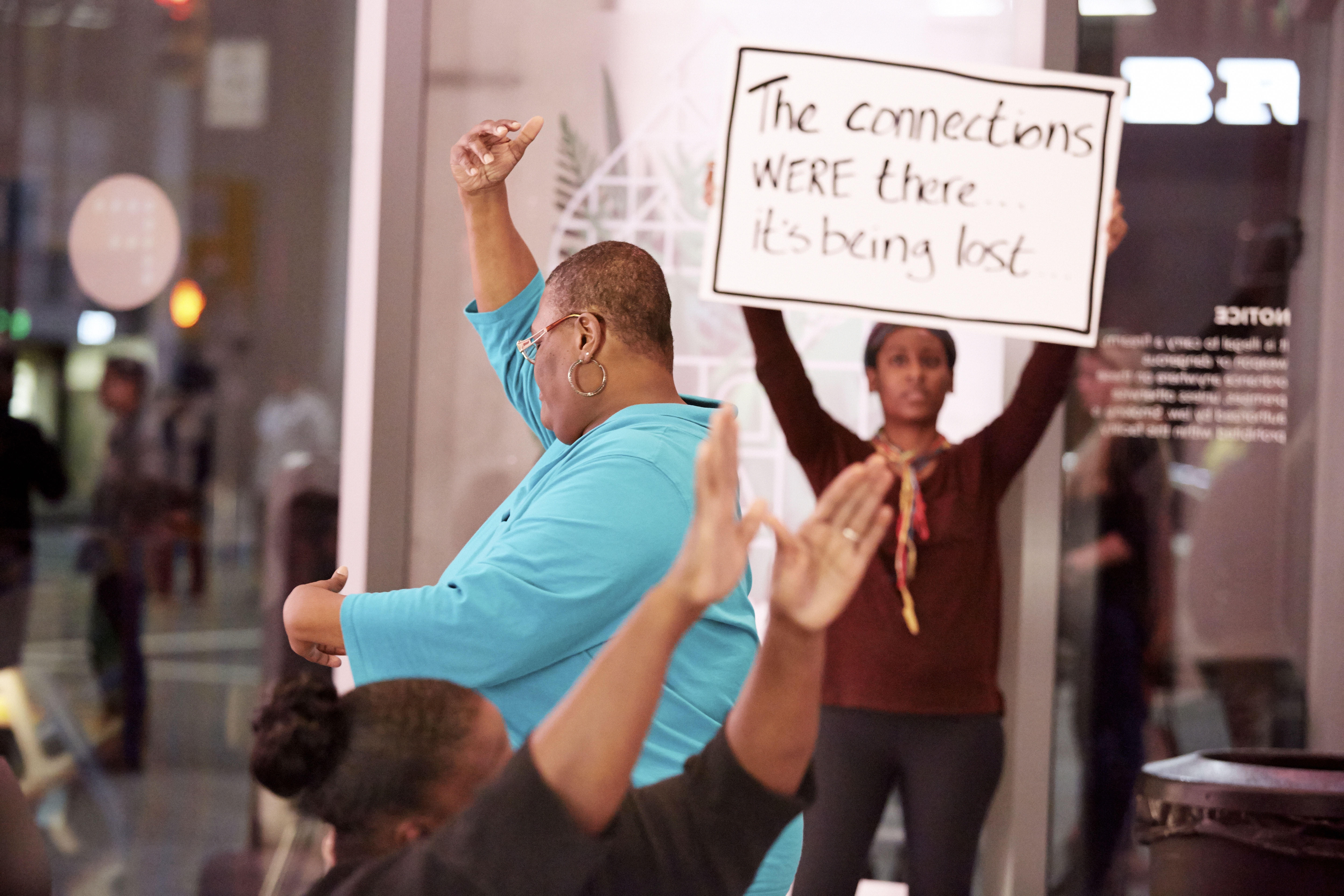

As an artist who is engaging in and with the community of Over-the-Rhine, and who is interested in making art that facilitates voice and connections among people who might not otherwise connect, who makes work that prompts neighbors to listen to each other, perhaps even work together, there is a question that I ask myself, and that I feel is essential for all artists to ask at all stages of development of a community-engaged art work:

Who best speaks for a group or community?

And this question sprouts a whole host of others:

To whose stories, or interpretations should we believe, listen to, act on? Whose experience of an issue is most authentic, holds authority? Who is outside and who is in – who speaks for whom – when someone visualizes/performs/describes/advocates on an issue?

Through whose lens is best to look? What do artists bring to the activity of framing and showing what might otherwise not be seen? What do we gain, and what do we lose, when we experience something through an artist’s interpretation vs. through the direct voices of impacted people? Can there be a combination of these two approaches that works best? What are some examples?

One art collaborative comes to mind that answers these questions in a powerful, honest, non-patronizing, grass-roots and effective way LAPD, the L.A. Poverty Department:

“Los Angeles Poverty Department was founded in 1985 by director-performer-activist John Malpede. LAPD was the first performance group in the nation made up principally of homeless people, and the first arts program of any kind for homeless people in Los Angeles.”

At LAPD, the artists are community people, and they are speaking for themselves.

Another example that has informed my working in Over-the-Rhine and now in DC: self-described maintenance artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, granddaughter of Marcel DuChamp, and “since 1977 the unsalaried Artist in Residence of the New York City Sanitation Department.” In talks I heard her give at Open Engagement 2014, Mierle told us the story of working with men who operated service trucks (snowplows, street sweepers) to choreograph ballets with their machinery. As wonderfully crazy as it sounds, I saw the work bring tears to the eyes of many in the room when she showed her video. Here’s how she approached creating it – she brought these guys into a room (made sure they were on the clock, getting paid for their time and expertise) and said, “I’d like to create a ballet with you and your trucks. What can they do?” And though it took time for them to understand (or maybe believe) what the hell this woman was asking, slowly but surely they started to create the choreography, giving ideas for what they knew would work well, rejecting ideas Mierle posed that they knew would not. They authored the work, facilitated by Mierle who served as the lead or initiating artist. What she did not do was gather them all, start telling them her choreography and ask them to carry it out.

Grounded in and informed by the work of artists like LAPD and Ukeles, I have to agree that the most respectful thing in this kind of social practice art is to set it up so that the people about, or for, or with whom the art is being made speak for themselves. I still have a lot to learn and develop to do this really well. But this question of who speaks is a hard one that we who are engaging in this kind of work must ask ourselves, not just at the beginning but throughout the development of any single work, body of work, lifetime of work.

Finally, the question of who speaks is linked to another:

What “qualifies” an artist to work in a community?

Should artists live in a place for their work there to be most authentic and grounded in the realities of that place? What if they don’t?

I don’t live in Over-the-Rhine, but I’ve worked there on and off since 1983, our daughter went to school there, I keep returning. Does loving a place, plus being a tax-paying city resident serve as ample qualification, or stake? My “positionality” as they say, has been questioned critically in the academic environment where I’m getting my MFA, an important challenge to pose, one which prompted me to think hard about this. In this particular case – the kind of work I’m doing and in this specific neighborhood – I came to the strong clear conclusion that all the ways I’m connected to OtR combined with my insistence on collaborating with others who do live and work there, provides qualification that I feel comfortable with. Over-the-Rhine people seem ok with it as well. I’ve not once had anyone in the community challenge my work there. Not yet at least. I hope anyone who does have that question engages with me, struggles with it with me.

The questions of “who speaks?” and “what qualifies?” really circle back to the issue of time – the longer an artist has to develop relationships in a place, the more likely they will value and be able to use their work to put forward the voices of the people; and the more possible to become a genuine member of the community, even if literal residency is not part of the picture.

So, rules for artists working in a place that’s not their place?

It might be best to conclude with one wise word from someone who’s been working in communities as a social practice artist longer than I. At Open Engagement this year in Pittsburgh, my Cincinnati artist friend Anissa Lewis asked keynote speaker, artist and 2014 MacArthur Fellow Rick Lowe how to best approach working with a community for the first time.

Rick’s response, “Sloowly.”

See you in the neighborhood,

Mary Clare

1 Comment

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

Mary Clare- beautifully written. I often think of the community artist or project lead’s role as catalyst, pot-stirrer, observer. I like Rick Lowe’s advice to approach the work sloooowly. As artists, we’re often used to providing our own interpretation via our art form(s)…it can be a challenge to step back, listen, and work to reflect what is being heard. I’ve also found that community artists can have a ton of impact on communities that they don’t live in, but are connected to- b/c they can serve the role as catalyst and provide a bit more objectivity. Creating projects that the community loves, owns, and will continue when the catalyzer moves on is vital.